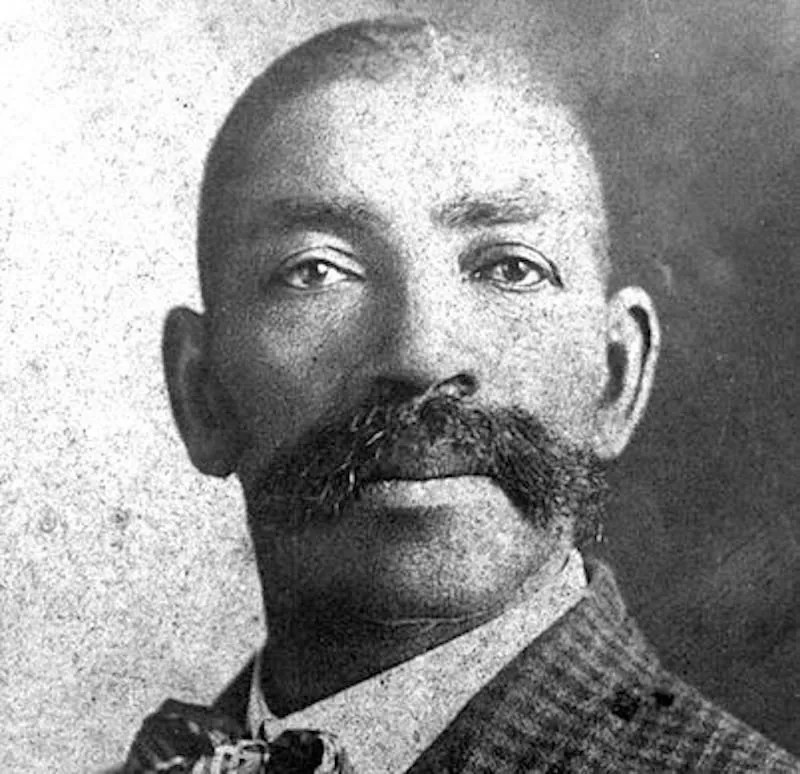

Bass Reeves (born: 1838- Died: 1910)

Right now, we see white folk dressed as cowboys, exalting the ‘Old West’ and how America expanded the nation west due to the ruggedness and tough determination of the Cowboy. What they fail to let you know is that: One in four cowboys in the ‘Old West’ was Black, although you would never know it in reading stories told in popular books and movies.

In fact, it’s believed that the real “Lone Ranger” was inspired by a Black American man named Bass Reeves. Bass Reeves (July 1838 – January 12, 1910) was an American law enforcement officer. He was the first Black deputy U.S. marshal west of the Mississippi River. He worked mostly in Arkansas and the Oklahoma Territory. During his long career, he had on his record more than 3,000 arrests of dangerous criminals and shot and killed 14 of them in alleged self-defense.

In 1838—nearly a century before the Lone Ranger was introduced to the public—Bass Reeves was born into slavery in the Arkansas household of a white man, William S. Reeves. In 1846, the household moved to Paris, Texas. When the Civil War began in 1861, the father, William Reeves, made Bass accompany his son, George Reeves, to fight for the Confederacy.

It was at this time, during the Civil War, that Bass escaped to Indian Territory. The Indian Territory, known today as Oklahoma, was a region ruled by five Native American tribes—Cherokee, Seminole, Creek, Choctaw and Chickasaw—who were forced from their homelands due to the Indian Removal Act of 1830. While the community was governed through a system of tribal courts, the courts’ jurisdiction only extended to members of the five major tribes. That meant anyone who wasn’t part of those tribes—from escaped slaves to petty criminals—could only be pursued on a federal level within its boundaries. It was against the backdrop of the lawless Old West that Bass would earn his formidable reputation.

Upon arriving in the Indian Territory, Bass learned the territory and the customs of the Seminole and Creek tribes, and learned their languages. After the 13th Amendment was passed in 1865, abolishing slavery, Bass, now formally a free man, returned to Arkansas, where he married and went on to have 11 children.

After a decade of freedom, Bass returned to the Indian Territory when he was recruited to help rein in the criminals that plagued the territory. Bass worked under the infamous hanging judge, federal judge Isaac C. Parker, who had recruited 200 deputy marshals to calm the growing chaos throughout the West.

The deputy marshals were tasked with bringing in the countless thieves, murderers and fugitives who had overrun the expansive 75,000-square-mile Oklahoma territory. Able local shooters and trackers were sought out for the position, and Bass was one of the few Black people recruited.

Standing at 6 feet 2 inches, with proficient shooting skills from his time in the Civil War and his knowledge of the terrain and language, Bass was perfect for the challenge. Upon taking the job, he became the first Black deputy U.S. marshal west of the Mississippi.

As deputy marshal, Bass is said to have arrested more than 3,000 people and killed 14 outlaws, all without sustaining a single gun wound, writes biographer Art T. Burton, who first asserted the theory that Bass had inspired the Lone Ranger in his 2006 book, Black Gun, Silver Star: The Life and Legend of Frontier Marshal Bass Reeves.

At the heart of Burton’s argument is the fact that over 32 years as a deputy marshal, Bass found himself in numerous stranger-than-fiction encounters. Also, many of the fugitives Bass arrested were sent to the Detroit House of Corrections, in the same city where the Lone Ranger would be introduced to the world on the radio station WXYZ on January 30, 1933.

In addition to his wide-ranging repertoire of skills, Bass took a creative approach to his investigations, sometimes disguising himself or creating new backstories in order to get the jump on his targets. He was fiercely dedicated to his US Marshal’s job. Bass was widely known to be incorruptible and strong moral character, and had a strong dislike for folk who tried to pay him off or shake him down. He even arrested his own son, Bennie, for murdering his wife. In Bass’ obituary in January 18, 1910, edition of The Daily Ardmoreite, it was reported that Bass had overheard a marshal suggesting that another deputy take on the case. Bass stepped in, quietly saying, “Give me the summons.” He arrested his son, who was sentenced to life in prison.

The legendary lawman was eventually removed from his position in 1907 when Oklahoma gained statehood. As a Black man, Bass was unable to continue in his position as deputy marshal under the new state laws. He died three years later, after being diagnosed with Bright’s disease, but the legend of his work in the Old West would live on.

Although there is no concrete evidence that the real legend inspired the creation of one of fiction’s most well-known cowboys, “Bass Reeves is the closest real person to resemble the fictional Lone Ranger on the American western frontier of the nineteenth century,” Burton writes in Black Gun, Silver Star.

End note:

Bass Reeves story was not isolated. In the 19th century, the Wild West drew Blacks who escaped slavery with the hope of freedom and wages. When the Civil War ended, freedmen came West with the hope of a better life where the demand for skilled labor was high. These Black Americans made up at least a quarter of the legendary cowboys who lived dangerous lives facing weather, rattlesnakes, and outlaws, while driving cattle herds to market.

While there was little formal segregation and a great deal of personal freedom in frontier towns, Black cowboys were often expected to do more of the work and the roughest jobs compared to their white counterparts. Loyalty did develop between the cowboys on a drive, but the Black cowboys were typically responsible for breaking the horses and being the first ones to cross flooded streams during cattle drives. In fact, it is believed that the term “cowboy” originated as a derogatory term used to describe Black “cowhands.”