In the Late 1800’s, George H. White’s bold legislative proposals combating disfranchisement and mob violence in the South distinguished him from his more reserved white contemporaries. As the lone African–American Republican North Carolina Representative, from 1897-1901, White spoke candidly on the House Floor, confronting Booker T. Washington’s call to work within the segregated system. The onslaught of white supremacy in his home state assured White that to campaign for a third term would be fruitless, and he departed the chamber on March 3, 1901. It would be 28 years before another black Representative set foot in the Capitol. White declared in his final months as a Representative, “This, Mr. Chairman, is perhaps the negroes’ temporary farewell to the American Congress…but let me say, Phoenix–like he will rise up someday and come again.”

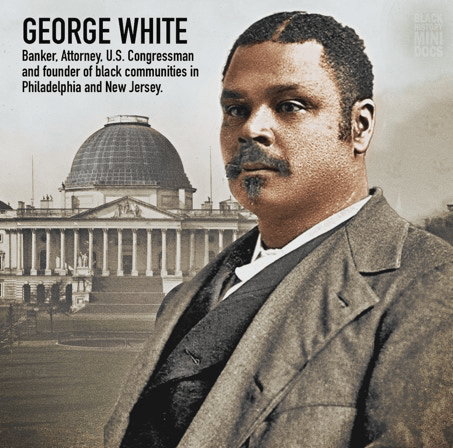

George Henry White was born in Rosindale, North Carolina, on December 18, 1852. His father was a free, working–class farmer, and his mother was a slave. White boasted Native–American and Irish ancestry as well as his African heritage and was notably light–skinned. At the end of the Civil War, the 14 year old White helped out on the family farm and assisted in the family’s funeral home business while intermittently attending public schools in Columbus County, North Carolina. In 1873, he entered Howard University in Washington, DC, graduating in 1877. White joined the North Carolina bar in 1879, and served as the principal at several black public schools. He married Fannie B. Randolph in 1879 and, six years after her death in 1880, he married Cora Lena Cherry. White had four children, three daughters with his first wife, and a son with his second wife.

White’s political career began with his election to the North Carolina house of representatives in 1880. That same year, he served as a delegate to the Republican National Convention. White initially focused on legislation pertaining to education, securing funding and authorization to open four black normal schools and provide training for black teachers. After establishing a second residence in Tarboro, North Carolina, he was elected solicitor and prosecuting attorney in 1886 in the “Black Second” district, which had a large black majority.

In 1888 and 1890, White reluctantly deferred candidacy for the district’s congressional seat to his brother–in–law Representative Henry Cheatham, whose calculated, conciliatory demeanor contrasted with White’s forthright, demanding, and unyielding personality. Cheatham lost his 1892 re–election campaign, and though the two men had an uneasy relationship, they were not outright political enemies until White made a serious bid for the Tarboro congressional seat in 1894. Cheatham planned to capitalize on the redistricting that added a large number of black voters in north. The brothers–in–law friendship disintegrated until 1898, when Cheatham relented, supporting White for a second term.

In 1896, White handily defeated Cheatham for the nomination. Possessing the full support of the Republican Party, White appealed to the Populists (a national third party made up of primarily disenchanted and economically depressed farmers) to avoid suffering a split in the Republican ticket. White distanced himself from the national Republican adherence to the gold standard and embraced the Populist platform calling for the free coinage of silver. White also benefited when a friendly 1894 state legislature reversed many of the Democratic election laws that impeded African–American voters—each of the three parties provided a judge and registrar at every polling place to ensure a fair election. Turnout among black voters in North Carolina rose to record levels of more than 85 percent. White won the congressional seat with 52 percent of the vote.

The only African American in the 55th Congress (1897–1899), George White was part of a large Republican majority that was swept into office on the coattails of presidential victor William McKinley. He received a seat on the Agriculture Committee, an assignment that recognized the large number of farmers among his constituents.

White’s focus in Congress in the late–19th century was defending the civil rights of his black constituents. For instance, White offered a resolution providing relief for the widow and surviving children of a black postmaster murdered in Lake City, South Carolina. The man and his infant daughter were killed by a white mob. Though the resolution was read aloud on the House Floor, White never spoke at length about the tragedy because Representative Charles Bartlett of Georgia objected to his request to elaborate. White also sought to commission an all–black artillery unit in the U.S. Army. At the end of the session, White called on President McKinley to discuss honoring black soldiers fighting in the Spanish–American War. Finally, White unsuccessfully sought $15,000 in federal funding for an exhibit on black achievement at the 1900 Paris Exposition.

Returning home to campaign for re–election, George White was the primary target of white supremacist politicians, who feared a renewal of the Republican–Populist political fusion. The Raleigh News and Observer was particularly scathing, alleging White was the mastermind behind the “Negro domination” of local politics and businesses and citing as proof his refusal to give his seat to a white Republican. White got support from white Republicans, that published a glowing endorsements, in addition to African American newspapers in the north. District Republicans expressed solidarity with White by renominating him without opposition in May 1898.

The white North Carolina Democratic newspapers replied to these endorsements with viciousness, declaring White had started an all–out race war. Also, White’s strong language about Black patronage, (which he basically said that white democrats are doing it, so why not black republicans?) at the convention infuriated white Populists, who broke from standing agreements and nominated their own candidate. The 1898 Black voter turnout was low, but the confusion of a four–way race divided the vote in White’s favor.

The post–election ramifications in North Carolina were tremendous. Democratic White supremacists in Wilmington, the biggest metropolis in the largely rural state, incited race riots in the city as an excuse to seize power from a fusion city government. Eleven black men were killed, and 25 were injured.

The bloody Wilmington riots, more like a massacre, troubled White as he returned to Washington for the final session of the 55th Congress, and he vented his frustration in his first substantive floor speech, on January 26, 1899. During a debate to extend the standing army after victory against Spain, White abruptly changed the subject to disfranchisement, arguing in favor of the bold proposal that states with discriminatory laws should have decreased representation in the U.S. House, proportionate to the number of eligible voters they prevented from going to the polls. “If we are unworthy of suffrage, if it is necessary to maintain white supremacy…then you ought to have the benefit only of those who are allowed to vote, and the poor men, whether they be black or white, who are disfranchised ought not go into representation of the district of the state.” Republicans greeted his speech with long applause.

The 56th Congress (1899–1901) convened with a Republican majority, and White was given a second assignment on the District of Columbia Committee, which administered the capital city’s government. But White’s second term was focused on his pursuit of anti–lynching legislation, despite President McKinley’s lack of support. On January 20, 1900, White introduced an unprecedented bill to make lynching a federal crime, subjecting those who participated in mob violence to potential capital punishment—a sentence equivalent to that for treason. White’s anti–lynching bill subsequently died in the Judiciary Committee.

White announced his intention not to run for renomination to the 57th Congress (1901–1903) in a speech on June 30, 1900, and declared his plans to leave his home. Several factors contributed to his decision. In 1899, the North Carolina state legislature followed the lead of neighboring states and passed new registration laws further restricting black voters. White also lost popularity within his own party. White Republicans resented his seemingly radical disfranchisement legislation and anti–lynching proposals, claiming he had belligerently “drawn the color line in this district.” Without strong Republican support, White had little chance of defeating his formidable Democratic opponent Claude Kitchin, scion of one of the most politically powerful families in the state. In addition, White was discouraged because noticeably fewer black delegates attended the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia in mid–June. Compounding his disappointment, the convention rejected the addition of anti–lynching and franchise protection planks to the national party platform. White noticed the strain on his family, particularly his sickly wife, Cora, for whom he believed another campaign would be fatal. “I cannot live in North Carolina and be a man and be treated as a man,” he lamented to the Chicago Daily Tribune. He told the New York Times, the “restrictive measure against the negro is not really political. The political part of it is a mere subterfuge and is a means for the general degradation of the negro.”

He encouraged southern black families to migrate west and remain farmers, not settling in colonies, but “los[ing] themselves among the people of the country.…Then their children will be better educated.” On January 29, 1901, White gave his famous valedictory address to the 56th Congress, predicting the return of African Americans to Congress. His speech, which filled more than four pages in the Congressional Record, pleaded for respect and equality for American blacks. “The only apology that I have to make for the earnestness with which I have spoken,” White concluded, “is that I am pleading for the life, the liberty, the future happiness, and manhood suffrage for one–eighth of the entire population of the United States.”

George White began a second successful career, as a lawyer and an entrepreneur. He opened a law practice in Washington, DC, in 1901. At the same time, he organized a town for black citizens to show that “self–sufficient blacks could not only survive but flourish, if…left alone in a neutral, healthy environment.” Dubbed Whitesboro, the town was built on 1,700 acres of land in Cape May, New Jersey, and by 1906, its population had swelled to more than 800 people. In 1905, White left Washington to start another law practice in Philadelphia. He also opened the People’s Savings Bank, to help potential black home and business owners. Though he never again sought political office, White actively supported the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909, and was a benefactor of the Frederick Douglass Hospital in Philadelphia. A year after his bank failed, George White died in Philadelphia on December 28, 1918.

Sources: